Thorsten Peger

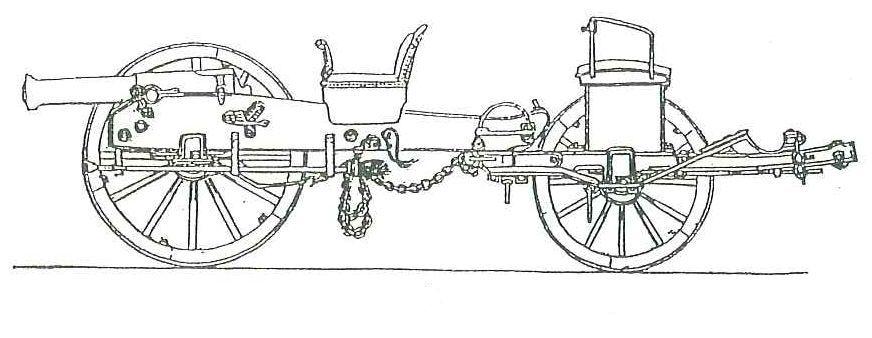

When, on 3 July 1866, the 1st (1st East Prussian) “Crown Prince” Grenadiers broke through Austrian lines during the battle of Königgrätz, Artilleriehauptmann August von der Groeben decided upon a risky course of action. Instead of retreating alongside other units, he pushed his men of the 4-pounder Cavalry Battery No. 7 of the VIII Artillery Regiment forward, and towards a sad immortality. In action near the village of Chulm, in what is today the Czech Republic, von der Groeben ordered the battery to limber up their eight 4-pdr M.1863 field guns and swiftly moved up to some 150 m in front of the Prussian line. The Prussians, exiting the village just as the guns reached their position, were immediately subjected to antipersonnel canister shot. The 94 artillerymen rapidly reloaded their guns, and managed to fire ten further rounds of canister shot, before being overrun by Prussian forces. Only minutes after unlimbering their guns, more than 50 men lay dead or wounded. Many of their horses had been killed, and only one gun was able to retreat.

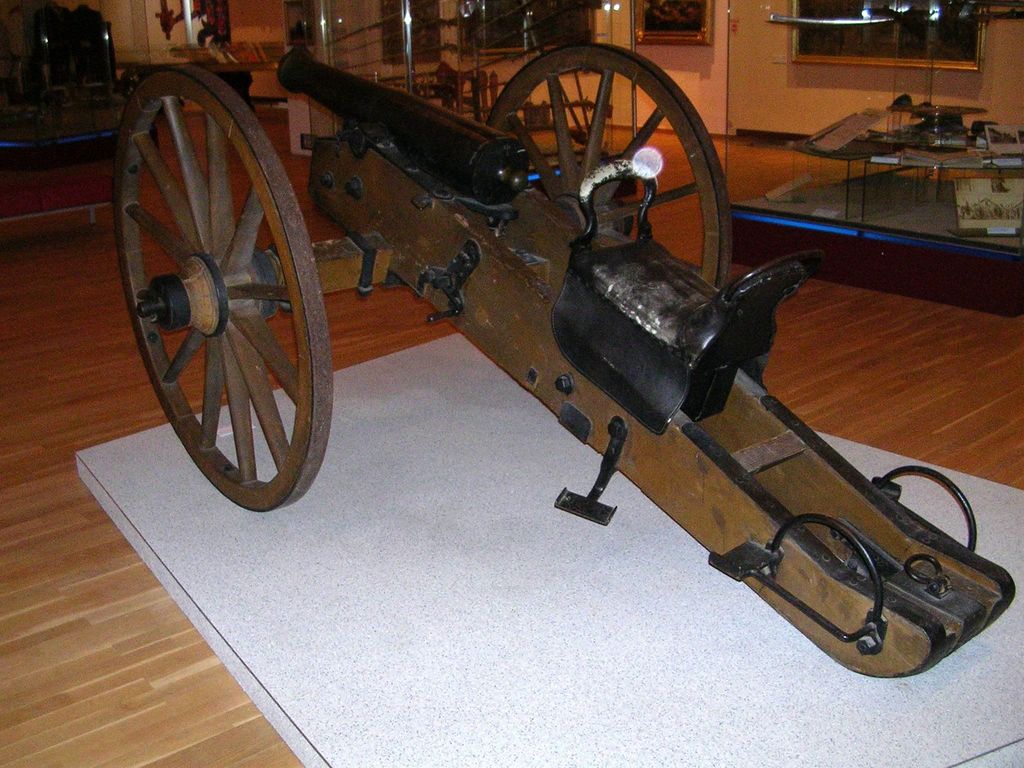

Today, an Austrian M.1863 4-pdr field gun remains on display at the Heeresgeschichtliches Museum in Vienna. It stands in front of a monumental Austro-Prussian War painting by Václav Sochor, ‘Die Batterie der Toten’, which illustrates the last seconds of Cavalry Battery No. 7 of the VIII Artillery Regiment of the Austrian Empire, the “battery of the dead”. The remarkable counter-offensive move Battery 7/VIII executed near Chlum was only possible due to the technical specifications of the recently-introduced M.1863, and so this gun merits closer examination.

Innovate or perish

The development and introduction of the M.1863 field gun falls into a period of technological change and uncertainty for artillery pieces. As a result of the widespread introduction of rifled muskets, field artillery pieces had largely lost their range advantage. The rapid development of new materials, innovative production techniques, and modern design considerations meant many mid-19th Century military thinkers were closely considering the best configuration and design for a field gun that would provide the best solution for upcoming wars – rifled guns or smoothbore types? Steel or bronze construction? Muzzle- or breech-loaders?

Rifled guns quickly proved their dominance during the War of 1859, but neither material choice nor loading style had yet displayed clear advantages. In 1861, the Prussians introduced a breech-loading gun made of steel; the Austrian army decided to stick with better-known technologies and materials. Steel was considered too expensive and a breech-loading mechanism too complex for the chaos, dirt, and grime of a battlefield. Accordingly, the Austrian M.1863 field gun material was developed as conventional muzzle-loading design cast from bronze.

Ahead yet behind

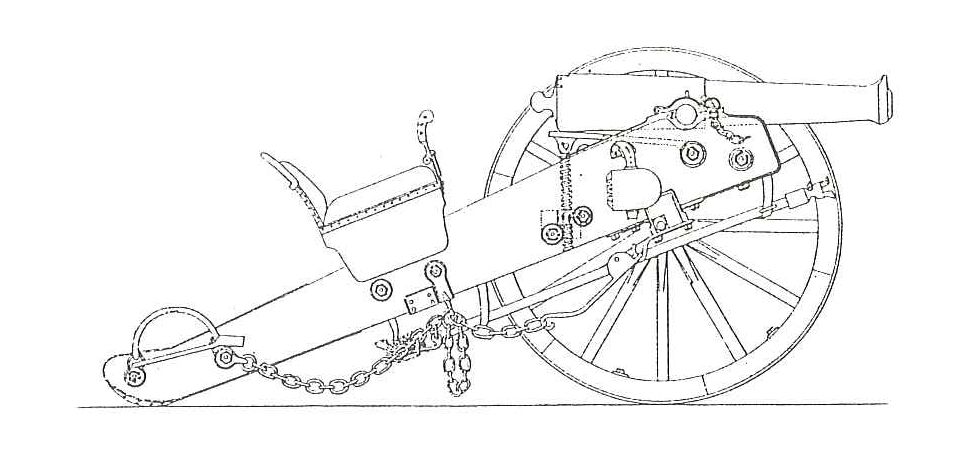

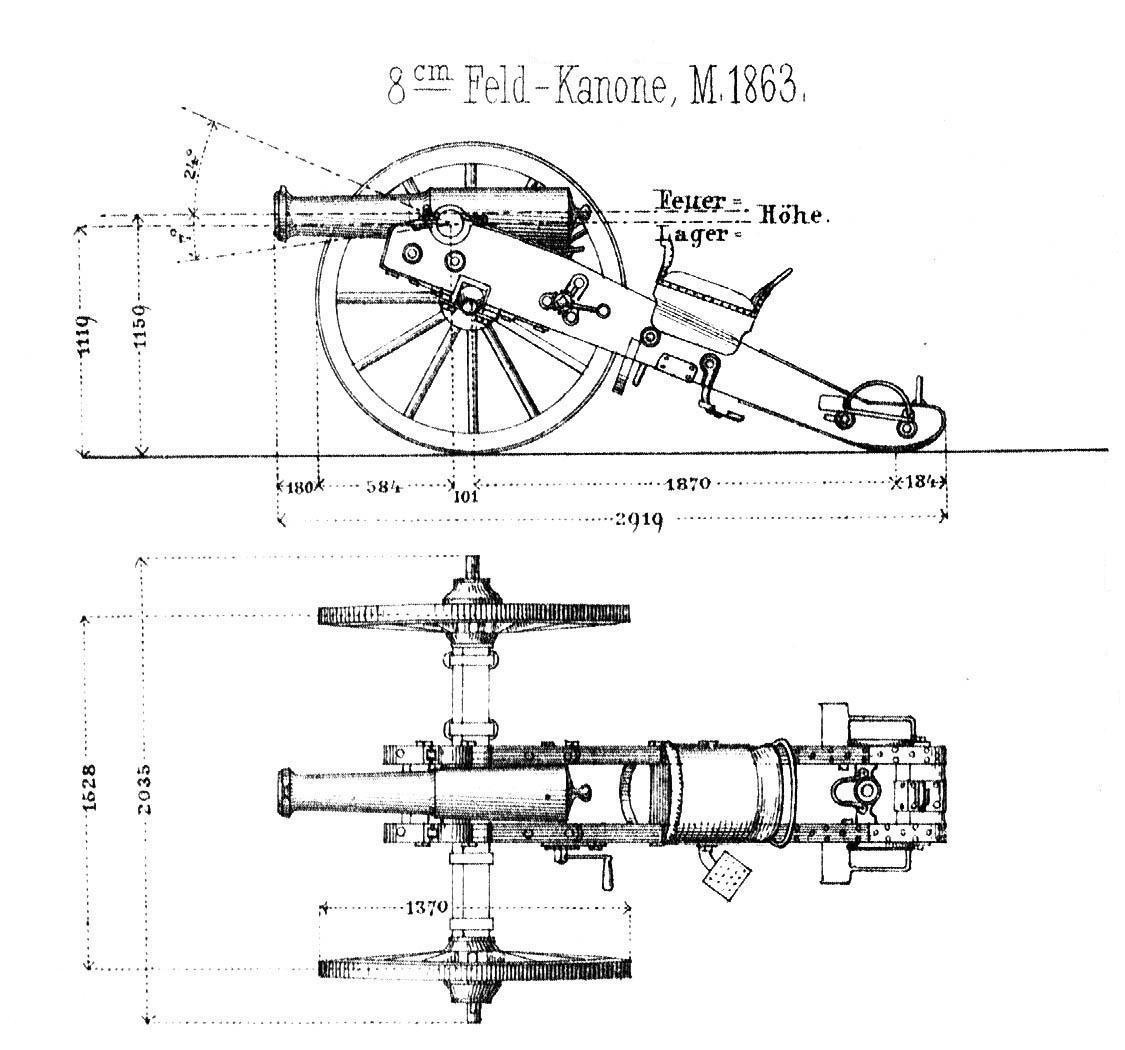

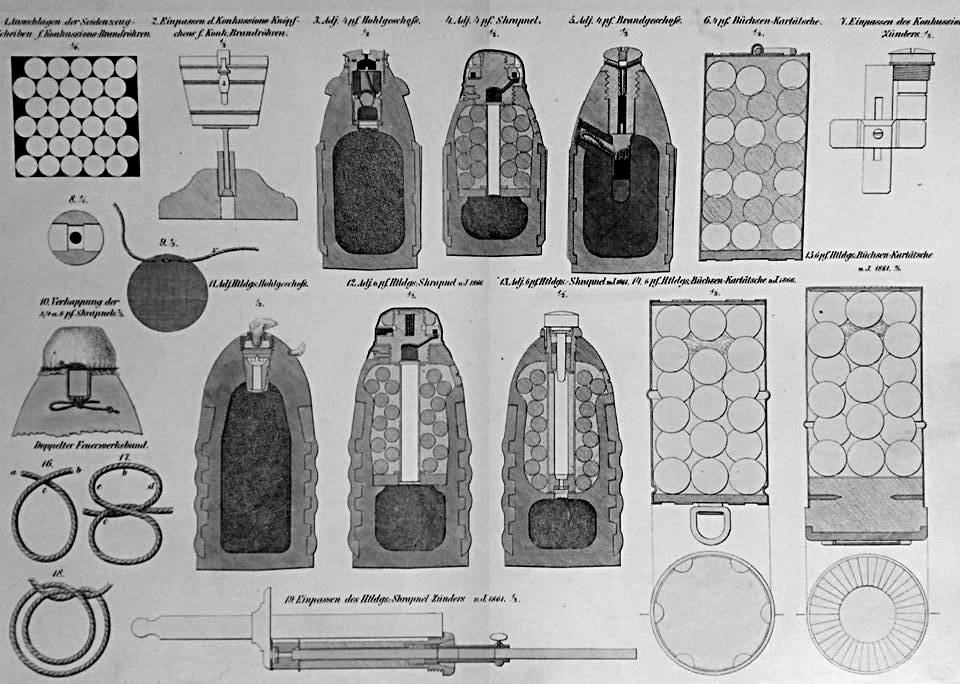

One upshot of the Austrian’s conservative thinking was a very short development time: within 6 months, during the winter of 1862/63, all of the new material for the weapon – including guns, carriages, and auxiliary equipment – was ready. Upon their introduction, the M.1863 field guns were actually some of the best field artillery guns of the period. The Austrians had more or less perfected the techniques used in producing rifled muzzleloaders. Three new field guns were adopted – a 3-pdr mountain gun, a lightweight 4-pdr for cavalry batteries and infantry brigades, and an 8-pdr field gun as a positionsgeschütz, a less mobile heavy gun. The M.1863 family not only replaced the heavier 6- and 12-pdr smoothbore guns in service, but also all howitzers. The design of the M.1863 guns and carriages was such that they were capable of delivering both direct- and indirect-fires. Four types of ammunition were adopted: explosive, shrapnel, and incendiary projectiles, as well as canister rounds. For the 4-pdr gun, ranges of 3,375 and 1,500 metres were achieved for the explosive and shrapnel projectiles, respectively. At the time of its introduction, the 4-pdr easily outranged many heavier, older guns. With a barrel weight of only 470 lbs, it had an impressive range-to-weight ratio and allowed for high mobility with a lightweight carriage.

Austrian commanders began to consider high mobility the defining feature of the new field guns. During the Second Schleswig War of 1864, for example, commanders were thrilled that batteries of 4-pdr guns could keep up with infantry along broken-up terrain and muddy roads in the winter environment. And whilst the Prussian guns are rightly lauded for their performance during the War, the highly-mobile Austrian M.1863 4-pdr was still able to dominate the Danish large calibre smoothbore guns. On 4-5 February 1864, Austrian Foot Battery No. 5, armed with 4-pdr M.1863 guns, fought alongside a Prussian battery against three Danish fortifications of the Danevirke line – the aggressors were able to silence Danish guns in short order.

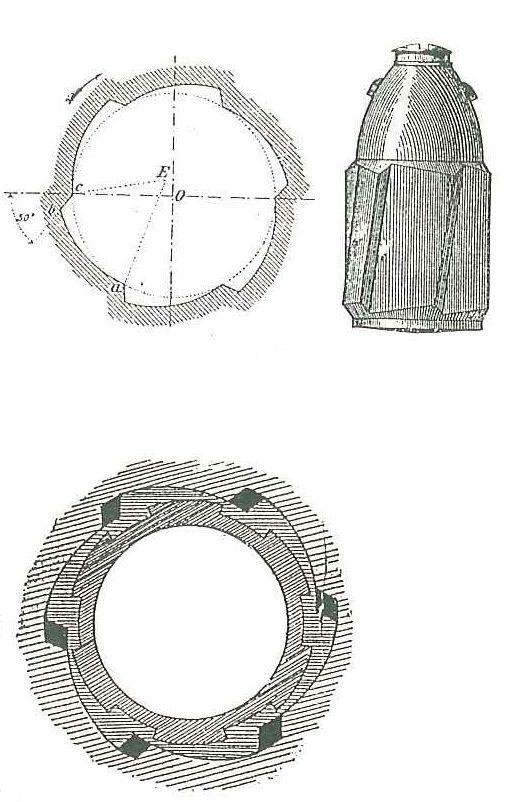

During the Austro-Prussian War, the 4-pdr and 8-pdr guns were even able to outclass the Prussian 6-pdr breech-loaders in in terms of mobility, and were reloaded faster than the Prussians or other observers expected. Ortner, 2007 states that Austrian muzzle-loading guns were even faster than Prussian breech-loading designs under field conditions. This technical dominance resulted from extensive testing. After suffering defeat at the hands of French forces in the Franco-Austrian War of 1859, the Austrian artillery committee did not simply adopt the French La Hitte system for rifle muzzle-loading guns, but instead tested a range of different rifling and gun designs, such as the Schießwoll gun, eventually settling on the domestically-developed Bogenzug system (derived from the earlier Lenk system). Six (4-pdr) or 8 (8-pdr) wedge-shape rifling grooves were cut into the barrel to accept projectiles which were covered with a tin mantlet which fitted into the rifling. This allowed for ease of loading and reduced windage to a minimum, improving ballistics and range.

Despite these commendable characteristics, the M.1863 was already obsolescent as it was being introduced. The limits of the materials and design had been reached. Conventional cast bronze guns could not withstand the more powerful charges entering service, and muzzle-loading systems would always have obstacles of windage and speed of loading to overcome. In breech-loading designs the projectile was able to positively engage the rifling of the gun and provide a tight gas seal. So, whilst the M.1863 gun may have marked the apex of the development for muzzle-loading, rifled cast bronze guns, the age of such weapons had long begun to fade.

Technical Specifications (4-pdr. M.1863 field gun)

Type: Rifled muzzle-loading gun

Period: Mid-19th Century

Region: Austria

Construction Cast bronze

Length of barrel: 1,383 mm

Weight of barrel: 213 kg (470 lb)

Calibre: 8 cm

Range: 3,375 m (explosive) / 1,500 m (shrapnel)

Width of carriage: 1,528 mm

Overall length: 2,919 mm

Bibliography

Criste, Oscar. 1904. ‘Groeben, August von der’ in Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie. Volume 49 (1904), pp. 556–557. Munich: Historische Kommission bei der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Müller, Friedrich. 1864. Das österreichische Feld- und Gebirgs-Artillerie-Material vom Jahre 1863. Vienna: Verlag von Carl Gerold’s Sohn.

Ortner, Christian M. 2007. Die österreichisch-ungarische Artillerie von 1867 bis 1918: Technik, Organisation und Kampfverfahren. pp. 59-72. Vienna: Verlag Militaria.

Riedl, Joachim. 2016. ‘Schlacht bei Königgrätz: Finale in Böhmen’. Die Zeit. 4 July. <https://www.zeit.de/2016/28/schlacht-bei-koeniggraetz-taktik-boehmen-oesterreich/komplettansicht>

Line drawings from Müller, 1864 except where noted. Other images courtesy of Jiri Vrba.